Ancient Eleutherna

Ancient Eleutherna: the dorian city-state of rethymno

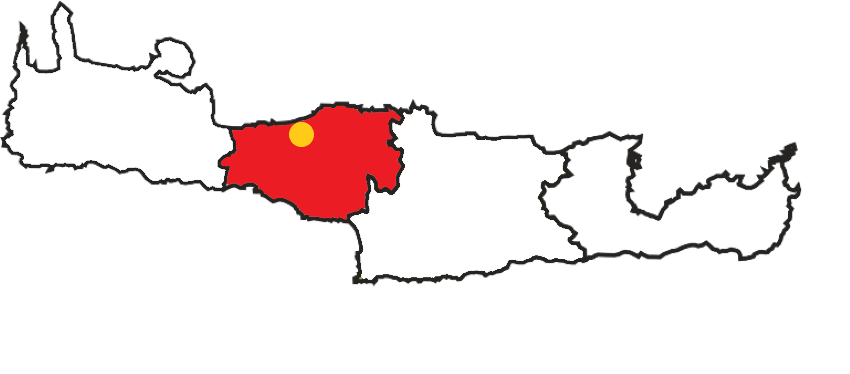

Ancient Eleutherna was a Dorian city-state and is located 25 km southeast of Rethymno in the Rethymnon regional unit. The site is about 1 km south of the modern village of Eleutherna, about 8 km north east of Arkadi Monastery. It flourished from the Dark Ages of Greece’s early history (1200 BC–800 BC) until Byzantine times and was one of the most important and influencial city-states in ancient Crete.

Name origins

There are three different versions of how the city got its name.

Some people claim that Ancient Eleutherna, alternatively called Apollonia, was named after the Olympian god Apollo, who had the epithet Eleuthiros (meaning: free).

Apollo possibly was the god worshipped in this city-state.

Coins found make a strong case that the first version is more accurate than the other two. The coins are displayed in the Archeological Museum of Chania.

Another version claims that the city was named after Eleuthereas, one of the Kouretes (one of the local soldiers guarding the entrance of Ideon Cave, where Zeus grew up).

Finally, we have the version that the city was named after Demeter Eleuthous (the Olympian goddess of the harvest and agriculture).

This suggests that Demeter may have been worshipped in the region, possibly with a local cult that honored her under this epithet associated with the concept of freedom or liberation (eleutheria in Greek means “freedom”).

History of Ancient Eleutherna

The origins of Eleutherna date back to the 9th century BC, during the Geometric period, when the Dorians colonized the city on a steep, naturally fortified ridge at 380 meters above sea level.

Early artifacts indicate that Eleutherna had ties to the Minoan civilization, evident in its pottery and architectural styles.

The city’s strategic location, between ancient Kydonia (todays Chania) and Knossos, at the crossroads of important trade routes, contributed to its prosperity, making it a thriving center of culture and commerce.

The Dorian city evolved in the Archaic Period in a similar vein as did Lato and Dreros, its contemporaneous Dorian counterparts.

In 220 BC, the city of Eleutherna sparked the Lyttian War by accusing the Rhodians of assassinating their leader Timarchus.

The Eleuthernans ultimately declared war on Rhodes. During the subsequent conflict, Eleutherna first joined forces with Knossos and Gortyna but was compelled to switch sides by the Polyrrhenians and join the opposing coalition led by Macedonian king Philip V.

During the Roman conquest, the city defended successfully against Quintus Caecilius Metellus’s attack in 68 BC but finally succumbed after a betrayal.

During the Roman occupation, Eleutherna was an important Roman provincial city, benefiting from infrastructure like aqueducts, baths, and amphitheaters until the catastrophic earthquake of 365 CE.

The city’s final abandonment was during the Byzantine era, in 796, after the continuous attacks from the Arab caliphat and another catastrophic earthquake.

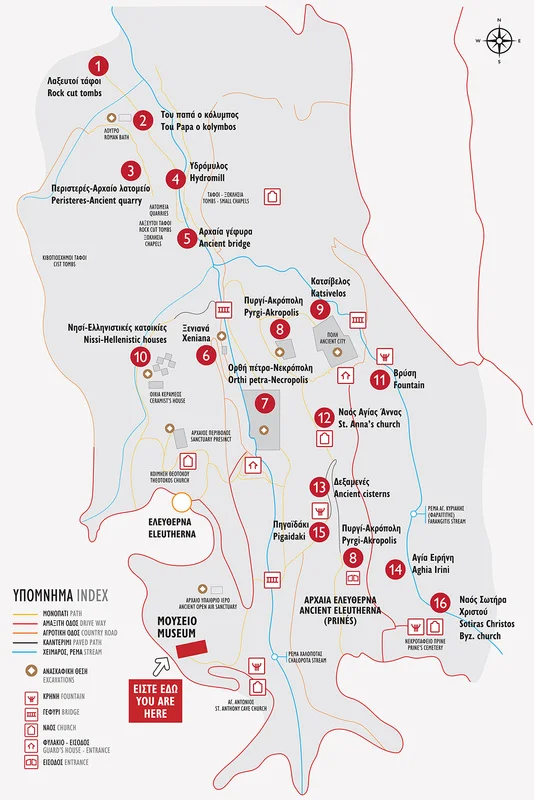

The Archaeological Site

The archaeological site of Ancient Eleutherna is a treasure trove of history, with significant finds that shed light on ancient life, art, and religion. The city was built on two hills (Prines or Pyrgi and Nisi Hill) and is divided into multiple areas. This archeological site is not like others because the areas to visit need a bit of patience and walking to reach.

Some of the most notable findings from the excavations were (not in order):

1) The Eleutherna Tower NO. 8 (next to 14)

Located on the Prines/Pyrgi hill, at the southern entrance of the Acropolis, this tower was built before the Roman period and served as a defensive stronghold, guarding the only entrance to the hilltop and the city of Ancient Eleutherna.

During the Roman attack, the city managed to defend successfully due to its location. The tower most likely was rebuilt and further fortified during the Byzantine era.

2) The Massive Rock-cut Cisterns no. 13

Impressive pillared cisterns carved in the rock on the south side of Prines/Pyrgi hill. An arched aqueduct delivered water to the city on the hill’s eastern side.

The construction of the cisterns is dated to the Roman period, but an earlier period shouldn’t be ruled out. Their size is impressive and you can inspect them in person by entering inside.

3) Agia Anna Church no. 12

The church of Agia Anna (Saint Anna) is believed to have been constructed in the Early Christian/Early Byzantine period, likely around the 6th century AD. Evidence suggests that it was part of a larger building complex. Agia Anna is one of the many churches in the area showcasing the transition of Ancient Eleutherna from a pagan city to a Christian center.

4) The Acropolis no. 8 (next to 9)

Built on the summit of Prines Hill, the Acropolis served as the heart of the city.

In its vicinity, the excavations unearthed crucial religious, administrative and defensive structures.

Also, many artifacts were recovered, such as terracottas, inscriptions, pottery and treasury.

Besides having great panoramic views, the Acropolis was a fortified area that served as the political and religious center.

Visitors can see remnants of walls, towers, and public buildings.

5) The Necropolis of Orthi Petra No. 7

Located on Prines Hill, west of Eleutherna, the Orthi Petra Necropolis has offered invaluable insights into ancient burial practices, social hierarchy, and trade.

Three burial methods were identified: cremation (primarily for high-status individuals), jar burials (for women, children, and elderly men), and simple burials for the lower classes.

Notable discoveries include:

The Heroon Tomb: The burial site for elite warriors, containing weapons, pottery, and gold ornaments.

Building M: Housing the graves of four noble women, with artifacts indicating aristocratic and priestly roles.

The Headless Male: A captive soldier, likely executed as retribution, found near a cremation site.

The Unlooted Tomb: Dating to 700 BC, it contained a gold-covered young couple and a unique jewel depicting a bee and a lily, symbolizing Cretan religious beliefs.

Artifacts from these discoveries are showcased in the Archeological Museum of Eleutherna, providing a glimpse into the city’s vibrant history and connections to the Mediterranean.

6) Katsivelos site no. 9

The Katsivelos site near Eleutherna offers a rich archaeological record spanning the Final Neolithic/Early Minoan through the Geometric period, providing insights into the region’s settlement patterns and cultural evolution.

Strategically located on a hill overlooking two rivers, the site reveals evidence of a small settlement that grew in complexity during the Middle and Late Minoan periods, reflected in substantial architecture and diverse pottery.

By the Geometric period, Katsivelos saw a decline in occupation, eventually being abandoned, likely due to regional urbanization trends.

The findings highlight the site’s significance in understanding the broader historical developments in Crete, including the rise and fall of the Minoan civilization and early Greek city-states.

Additionally, the site is also home to an early Christian basilica, dating to the 5th–7th centuries A.D.

This three-aisled basilica features two rows of columns dividing the interior, with the lateral aisles likely having a second floor.

The stone iconostasis is adorned with floral motifs and crosses, while the preserved mosaic floors display geometric and floral patterns, showcasing the religious and artistic evolution of the site well into the Early Christian period.

This addition highlights the site’s significance not only in prehistoric and Minoan times but also during the early Christian era.

7) The Basilicas of Agia Eirini and Agios Markos no.14

The Early Christian basilicas of Agia Eirini and Agios Markos on the eastern slope of Ancient Eleutherna highlight the site’s transformation during the Early Byzantine period.

These three-aisled basilicas were constructed using spolia from earlier Hellenistic and Roman buildings, reflecting continuity in the urban landscape.

Agia Eirini, noted for its mosaics, inscriptions, and references to local bishops, dates to the 5th century AD and likely fell to earthquakes in the 7th century.

Agios Markos features high-quality architectural elements reminiscent of designs from major Byzantine centers, emphasizing its significance within the regional ecclesiastical network.

8) Church of Sotiras Christos (Christ Savior) no. 16

The Church of Sotiras Christos, located on the eastern slope of Prines Hill within ancient Eleutherna, is a 5th-century AD Early Christian basilica.

The church was renovated in the 14th and then in the 16th century, where the southern church was added, dedicated to Saint John.

Today it hosts the cemetery of the modern Eleutherna village, surrounded by lush green and close to a fresh water spring. The older church bears frescoes from the 12th century, with the highlight being the Pantocrator on its dome.

9) Hellenistic Settlement at Nisi no. 10

The Hellenistic settlement at Nisi, located on a hill north of Eleutherna, showcases the city’s prosperity during the 4th to 1st centuries BC. Excavations have uncovered houses, pottery kilns, and streets, revealing a community deeply engaged in ceramic production and trade.

Pottery kilns and misfired fragments indicate that Nisi was a hub for crafting utilitarian and luxury ceramics for both local use and export. The settlement’s eventual abandonment in the mid-1st century BC, likely linked to the Roman conquest of Crete, marks a pivotal moment in Eleutherna’s history, shedding light on the dynamics of urban development and economic activity in ancient Crete.

10) Hellenistic bridge no. 5

The Hellenistic bridge at Eleutherna, built in the 3rd or 2nd century BC, spans the confluence of the Chalopota and Pharangitis rivers north of the city.

It played a vital role in facilitating communication and trade, connecting Eleutherna to regional centers like Sybrita and Lappa and later integrating into the Roman road network leading to Gortyn.

Constructed from robust limestone blocks, the bridge reflects the city’s prosperity and infrastructural advancements during the Hellenistic period.

Although partially preserved, its early 20th-century restoration underscores its historical significance as a symbol of Eleutherna’s connectivity and enduring legacy.

Just before reaching the bridge, we can see ancient carved tombs and the cavernous church of Saint Nicholas.

11) The quarries no. 3

The presence of limestone quarries near Eleutherna played a major role in the city’s growth. The city’s residences, public buildings, and defenses were built using limestone, which was easily accessible. The ancient quarry at Peristeres, with its intact support pillars, “benches,” and unfinished stone blocks, provides insight into the techniques used in antiquity.

Eleutherna Archaeological Museum

Opened in 2016, the Museum of Ancient Eleutherna is a state-of-the-art facility that complements the archaeological site.

Located near the excavation area, the museum houses a stunning collection of artifacts, including:

Pottery and Figurines: Ranging from Minoan to Roman times.

Jewelry and Weapons: Exquisite examples of craftsmanship.

Funerary Objects: Items from the Orthi Petra Necropolis, including gold wreaths and carved sarcophagi.

The museum’s interactive displays and detailed explanations make it an engaging experience for visitors of all ages.

From time to time, the museum houses other exhibitions in addition to its archeological displays. On my visit, it housed an exhibition about Pablo Picasso and how he was inspired by the Minoan civilization and the Minotaur.

Additional informations for the site

Eleutherna Village, Rethymnon

Caffeteria & W.C.

Adults 6€, over 65 3€. Youth up to 18, handicap and students, free.

Phone Number: +30 2831 028101

Closed (1st November- 30th March)

Usually visitors stay in this area up to 3-4 hours

Νο available Wi - Fi.

1st April - 31st October: 10:00 - 18:00, Closed on Tuesdays

unfortunately no infrastructure for handicap

How to Get There

Ancient Eleutherna is located approximately 30 kilometers southeast of Rethymno, making it easily accessible by car or organized tour.

By Car:

The drive takes about 40 minutes. There is parking available near the site and museum.

By Public Transport:

Buses to nearby villages, like Arkadi or Margarites, can get you closer, but a car or taxi is recommended for the final stretch.

By Guided Tour:

Many tour operators in Rethymno offer day trips to Eleutherna, often paired with other nearby attractions.

Conclusion

Ancient Eleutherna stands as a testament to the rich and diverse history of Crete, spanning from the prehistoric to the Byzantine era. Its strategic location, architectural remnants, and burial sites reveal a society deeply connected to Minoan, Greek, Roman, and early Christian traditions. The city’s religious and civic structures, including early Christian basilicas, highlight its role as a cultural and spiritual hub. Ongoing excavations continue to shed light on Eleutherna’s evolution, offering valuable insights into the island’s historical transformations. Today, the site remains a crucial link to Crete’s past, bridging ancient heritage with modern archaeological exploration.

ADDITIONAL TIPS FOR AN ENJOYABLE VISIT TO ancient eleutherna

Destinations near ancient eleutherna

More options for nearby locations to plan your vacations better!